March

Officer, I've got soup so wet you wouldn't believe it.

No pre-amble, I’m saving all my game for the ambling.

Events

A limping little round up of a half-month, for I have had the plague.

David Lynch at the close-up film centre dotted about the month

Thurs 13th

Morocco Bound Folk Sessions, £6.50

NRS Presents: No Teeth, Gross Misconduct, Citizen Above Suspicion at New River Studios, £9.90

SCOBE Live. 2 - GUITAR TRIO / Marriage Banxxxd / PEG / Scobe Collective at Spanners, £5

Fri 14th

Morocco Bound Presents: Hannah Archambault &Franzi, £12

Max Cooper at Roundhouse, resale

Crafting together workshop at SET social

BODY COUNT: Kuedo, Sully, Logos, Cloak of Kings, Klaar at Ormside, £12-14

Sat 15th

Shell Company & Older Brother / LINTD / Kincaid at Spanners, £12

Sun 16th

A slew of things at SET social Peckham!

UNFOLD at Fold

Spirit ࿓ Pause ❘❘ : Special Guest, Bake & Kit Seymour at Ormside, £12.70

Mon 17th

Glaive at KOKO, £22

Resonance poetry open mic at SET social

Rhodri Davies at Cafe OTO, £14

Tue 18th

The Common Press Poetry Night - March at the Common Press, £12

Rhodri Davies at Cafe OTO, £14

Wed 19th

Morocco Bound poetry open mic

Thurs 20th

Flöat, Oscar James + Henry Webb-Jenkins at the Ivy House, £9.38

Bookshop Sessions: Jazz Night at Morocco Bound, £6.50

Fri 21st

Jones/Ward/Lash at Morocco Bound, £12

Iniko at KOKO, £36.88

Pink Pilled: A Book Event at the Common Press, £13

Horse Hospital reopening - stacked!!!!

June McDoom at St Pancras Old Church, £18.15

Sat 22nd

Horse Hospital reopening - stacked!!!!

David Cronenberg & Howard Shore in Conversation at the Southbank Centre, £25+

Unbound presents: object blue [live], Metrist, NVST & DJ Winggold at Ormside, £15-20

Soheil Nafisi at King’s Place, £25-45

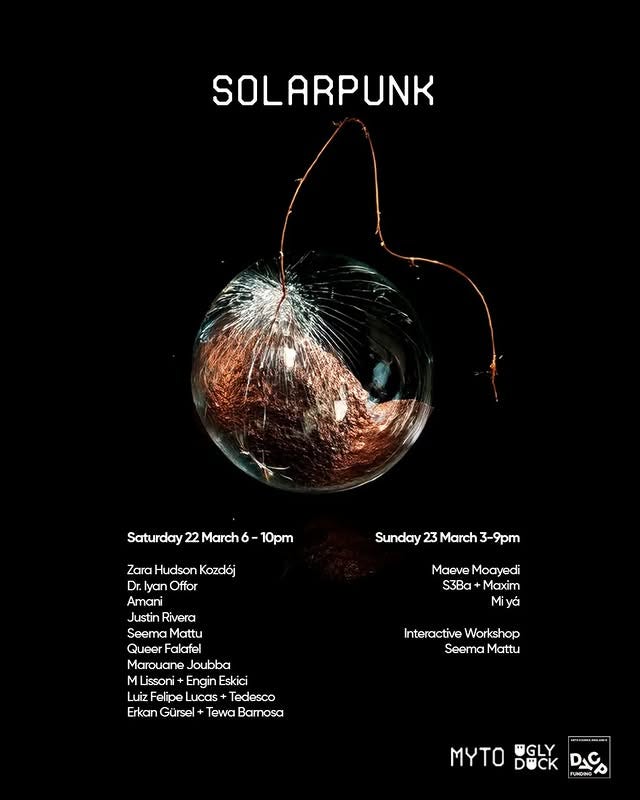

Solarpunk at ugly duck, £12-20

Sun 23rd

Nunhead Jazz Circle at the Ivy House Nunhead

Free Movements at Ormside

Concrete Garden: Fertile Ground at the Barbican

Folk of the Round Table at SET

Mon 24th

Avalon Choir

Wed 26th

Archiving as a communist inventory? with Agit Press at MayDay Rooms, free

Moonchild Sanelly at Village Underground, £22

Alina Ibragimova Plays Prokofiev at the Southbank Centre, £14+

Creative Encounters: Stacy Makishi at the Southbank Centre

Lene Otis Finn + }Ï{ + Finton Coin + Masa Nazzal at Cafe OTO, £12

Thurs 27th

Pierre-Laurent Aimard & Mathieu Amalric: Ravel at the Southbank Centre, £17+

Intergenerational Trauma and Decolonial Futures in Space Exploration at the Architectural Association,

Kellora at St Pancras Old Church, £14.30

a thursday meander (pt.6) at Spanners, £7-9

Lambert at King’s Place, £10-20

Fri 28th

Phase Group: TC LK (live), DJ Peanut, Rick Shiver at Spanners, £11

Sat 29th

After Dark: Colin Currie at the Southbank Centre, £12

Sun 30th

Folk of the Round Table at SET

Mon 31st

Bitmap and Music from the Sri Lankan Diaspora at Cafe OTO, £12

Notes on Handwriting

For those who would rather listen than read:

To avoid being dull I will start with Anne Carson, who avoids being dull by starting with Catullus, a Roman poet who lived in the first century BCE.

I tell you, Catullus, leave Troy, leave the ground burning, they did.

Look we will change everything, all the meanings,

all the clear cities of Asia you and me.

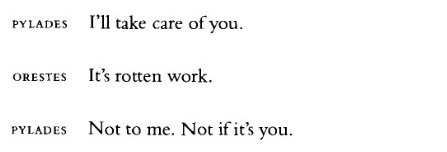

He is speaking to himself, here. Well, and perhaps it is only the fact that it’s Anne Carson that makes it read like romance to me, but doesn’t that sound like a love letter? A call to elope? Her translations have so much eternal romance to them, romance in a grand and timeless sense. She has a knack for landing upon phrases that feel well and truly uninflected by the awkward trademarks age and culture place on vernacular language. I would love to read Ancient Greek with her eyes, to see whatever truth is clearly visible to her. Among her most famous lines are these, from her translation of Euripides’ Oresteia,

I went to a talk she gave, perhaps a little over a month ago, where she spoke about handwriting and boxing and Parkinson’s disease. She has a very precise, soft, lucid way of speaking, and I kept thinking to myself that I want to grow old. I want to grow old and sit on my stoop and force grandchildren to drink foul medicinal tea and tell them that its good for them, and mostly when I am old I want to speak like Anne Carson: quiet, commanding a slight hush, sure that all around will comply in order to hear me.

You are five years old. You’re learning to write. The lines bend, sometimes to your will, sometimes under other forces more obscure to your faculties. You learn to shape letters, numbers, you grow up and your lines steady out. You marshal them, you make the most of yourself, become a gardener, a bookkeeper, an acolyte, a master, a pirate. You are no longer five. Your handwriting is in a stage of constant correction, of cursive guard rails.

I remember being fascinated with my parents’ handwriting as a child. The freedom and ease with which they wrote astounded me. And yet I sensed that there was some rule of freedom at play I’d no skill yet to discern. Because their handwriting was atrocious, illegible by the standards of my teachers, and yet it had a certain style that mine lacked, like mine hadn’t been lived in enough yet to have character. As if simply by carrying it around with you, the lines smooth from their childish tremouring into their natural distinguishing features. Like ageing changes your handwriting as it does the rest of you. And in a way, it does. Your wrists strengthen, you grow more hasty, then less. And then you are old, and you get to abuse your power by feeding foul tea to small children and pretending it’s good for them, and your handwriting shakes again, and becomes like a child’s.

And while I count graphology in with phrenology (both, after all, look for destiny in the spacing and cant of prominent features and lines), I do see the appeal. There’s something pleasingly mysterious about the precise character of handwriting, which seems to come about without us specifically willing it. This is, of course, when we speak of personal handwriting, not the work of calligraphers, and perhaps more specifically, the handwriting of people living through an age where we learn but do not often have occasion to practice it. My handwriting is less the product of rigorous study than feverish use and haphazard negligence.

But handwriting, like a dream, seems to come to us carrying the character of the unconscious, because we do not mean for it to look as it does exactly, it simply takes shape that way. And yet we are the tool and the hand that guides it! How can that be? But handwriting, like a dream, is a voice. Handwriting, which is not very like a dream at all, is a symbolic kind of disembowelling. Externalisation. We take what is inside of us, where it does not yet really exist, and we conduct it to the outside, where it begins to exist.

You understand me?

Handwriting, like a voice, exists inside you only as an idea, not as a form. It is part of you, it is an action you can take that will carry with it the physical thumbprint of yourself in its shape, something that will exist outside of your body and still be a part of you, like spitting on the ground. But not at all like spitting on the ground, because you will be able to tell at a glance that it is a part of you. You will look at a page of your own handwriting and receive the same note from your brain as if you were looking at your hand itself: “familiar. me.”

Other actions trigger this, of course. Someone’s gait is so distinctive as to be often instantly recognisable. But short of reading footprints, a gait cannot be read in separation of a body.

A voice is similar, distinguishes and characterises itself by belonging to you, and yet is only made recognisable once set free from your body to hush out into the world. Anne Carson sounded just like I thought she would.

And here’s the other thing that makes graphology tempting: handwriting, it seems, is hereditary in phenotype. Motor skills, yes, yes, but I must insist we give just an inch to mystery here. Reading through my grandparents’ letters, the odd E and G greet me with familiar intimacy; I see my mother’s vowels reflected back at me. I am filing away their handwriting along with these young versions of them I never knew, and it feels like shaking their hands. Of course, it also feels like a dreadful invasion of privacy. Reading someone’s private letters, notes to self, diary entries. That poem, Catullus, speaking to himself. Writing in his own lines to his own self. There is something of surpassing intimacy in someone speaking to themselves. Catullus, two thousand years ago, writing in his own hand1 to Catullus, telling himself to leave Troy, find spring.

Now the feet grow leaves so glad to see whose green baits

awaits.

Oh sweet don’t go

back the same way, go a new way.

Oh, sweet. Don’t go.

Studies have found that people speak to themselves as an externalised ‘you’ mostly in response to situations requiring direct behaviour regulation. I address myself out loud, as another person, when I sense that I need to pull myself together on some issue or another. I address myself as myself (self-talk using ‘I’) when I’m rehearsing speech or attempting to verbalise my interior life and thus shape it into some cohesive narrative. But when do I write to myself? When do I call myself, ‘oh sweet’?

It reads a little like Hafiz or another love mystic, always talking about the Beloved. One day I will write about the parallels of the Beloved in Hafiz with the role of Jesus in the writings of female christian mystics from the medieval period. One day I will have written about it all, and then I can rest. And then I will drink tea and sit on the stoop and keep chickens with my gnarled old hands and my hoard of handwritten diaries.

The dead complain of their burial, but they’d complain more if they knew what we did with their things, after. Please, go through all my notebooks and journals when I am dead. It is where I keep my soul, and they must be read or burned, or I would never move on.

So I wonder what part of himself Catullus felt that he put in his handwriting, and what he would have thought about the collapse of time and bodily integrity in the relics of scrolls holding his work.

To the best of my ability to research it, it seems that he would indeed have written his own poems, rather than dictated to a scribe. The internet provided me shockingly poor answers on this, though, so if you know more scrupulous sources or details about the writing practices of Roman Republican poets, PLEASE reach out.